|

на правах рекламы• How to Become a QuickBooks ProAdvisor in 3 Steps • купить лодочный мотор в екатеринбурге . Мы можем доставить покупку курьером в пределах Екатеринбурга. По Свердловской области и другим регионам страны доставку лодочного мотора можно заказать через транспортную компанию. Квадроциклы. |

SummaryVasily Surikov is a notable Russian master of history painting. He created seven large pictures on historical subjects, each taking several years of work, and also a great many studies, sketches and portraits for them. They show a variety of folk types and are characterized by a keen perception of historical atmosphere and importance of the events that the artist depicted. His vision expressed itself in the imagery, composition and colouration specific of bis painting. The master's works are in the same range as the masterpieces of Russian culture like Boris Godunov by Alexander Pushkin, War and Piece by Lev Tolstoy, Khovanshchina and Boris Godunov by Modest Musorgsky. The painter began his work in the 1880s, a period of thriving of realism in painting; he shared progressive democratic ideas of bis time and was closely linked with the Itenerants' Society. It was a time when a constellation of outstanding talents arose, yet Surikov was not lost among them; bis creative personality and specifically historical artistic mentality were unique. The story of Surikov's life shows that his artistic career was quite natural and expected. Vasily Ivanovich Surikov was born on January 12, 1848 in a Siberian town of Krasnoyarsk, in a very old Cossack family, whose members were of free, indepentent and unsubmissive spirit. From bis early childhood the painter was surrounded with the atmosphere of «old times», patriarchal mode of life, traditional clothes and folk tales. During his further life Surikov used to return to his native home and stay there for a long time. In 1870 the talented Siberian youth came to St. Petersburg and entered the Academy of Arts. In his years of learning be painted pictures dictated by the Academy programme, i. e. paintings on Riblical and mythological subjects. At the same time, completely on bis own, he started a series of realistic sketches from Russian history. A new period in Surikov's life began in Moscow, where he came to live after the graduation from the Academy of Arts. «In Moscow I found myself in the centre of Russian folk life and immediately found my way», wrote Surikov. The artist was attracted by views of the city, old Moscow architecture, the Kremlin, the Red Square, historical cathedrals. He became obsessed with the theme of Russian history: lie had a peculiar vision of historical events and eventually formed his own idea of history, which became the philosophical foundation of his art. In Surikov's notion, the people was the active force of history, he was interested in the relationship between the personality and the inevitability of social evolution. In his pictures showing Russia of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century Surikov revealed a tragic collision of the new social order, the Russian state entering the European scene, and traditional attitudes based on outdated social and religious conventions. Surikov was attracted by the rebelious spirit of the Russian people, the conflict between the personality and the state and the profundity of human feelings. He possessed a thorough knowledge of historical facts, though he was no theoretician but a painter with an acute sense of historical truth and poetic imagination. Surikov was a true realist, his pictures are genuine representation of history without stylization or idealization typical of official history painting. His main asset was realistic method in painting, the source of his imagery being impressions of contemporary life. However, he had a gift of seeing the historical roots of the present-day life, the gift of penetrating into the psychology of people of earlier times. He was a genius of historical reconstruction of facts and human feelings. Surikov's first large painting, the Morning of the Streltsy Execution (1881), was devoted to the time of Peter the Great, namely, the events of the end of the seventeenth century when the army of Streltsy supported by Princess Sophia rose against the young tsar. The riot of the Streltsy was severely supressed and ended in tortures and execution of those who had taken part in the riot. Surikov depicted the scene of the execution on the Red Square against the back ground of St. Basil's Cathedral, in the presence of Peter the Great and his associates. Epic in character and dramatic in its plot, the picture has no compositional centre. It consists of several groups: the Streltsy sentenced to death, wearing white shirts and with lighted candles in their hands, and around them, their grieving relatives and friends. «What I wanted to show is not the execution but the solemnity of the last minutes», wrote Surikov. We can see that he succeeded in showing what he intended to show. Each character represents a certain individual type, a bearer of certain pathetic feelings, e. g. the figure of the white-haired Strelets and the weeping child, the black-bearded Strelets and the young woman embracing him, the grief-stricken old woman and the frightened girl. But the most impressive is the red-bearded Strelets in fethers, wearing a red cap, his eyes fierce and loathing, fixed on the Tsar. The colouristic tonality of the picture is subdued, slightly darkened, which accentuates the white of the Streltsy's shirts and the flicker of candles. This adds to the scene an atmosphere of disquiet and alarm. The second great picture by Surikov is Menshikov in Beryozovo (1883), which was another link in the chain of the painter's philosophical and historical meditations about Russia. Alexander Menshikov, the most prominent statesman at the time of Peter the Great was the latter's close friend and associate in all newly introduced changes of the political and economic life of the country. After the Tsar's death he fell in disgrace and was dismissed from all his posts and exiled to a remote part of Siberia. The picture shows Menshikov with his family in a tiny log hut with a small frozen window, old icons in the corner and a glowing lamp in front of them. It is a striking psychological work revealing the depth of human emotions, with very accurate personal characteristics. In the centre of the picture is Prince Alexander Menshikov, once an enormously powerful and energetic man who had scaled the heights and now toppled back to the earth, passive and sulky like a beast at bay. He is engrossed in a continuous and torturing contemplation. Outwardly static, the picture is brought with inner dynamics; it has a strained and oppressive atmosphere of solitude. Next to Menshikov is his elder daughter Mary, a character of stupendous attraction. The silent agony of the slowly fading young girl emphasizes the misery of the father. The model for Mary had been the painter's wife, who was very ill and died young. Menshikov's son, Alexander is also deep in gloomy thoughts; and only the youngest daughter, a pretty girl, looks untroubled, absorbed in reading. The principal figures are entwinned in the composition, they are pressed together by the limited space of the room, this stresses the sensation of their common suffering: they are together in this fate. The dull colours of the picture enhance the pessimistic atmosphere of the scene. But inside the subdued palette there appear rich colouristic diversity, luxuriously painted brocade and velvet of the girls' dresses, the bleak, cold hues of the hore-frost on the window-pane, the golden light of the icon-lamp which falls on the old icons, and the gilt embroidery of the covers. Colouristically, this picture is considered the best work in the Russian painting of the nineteenth century. Pavel Tretyakov bought the picture for five thousand roubles and placed it in his gallery. The money enabled Surikov to take his wife and two daughters abroad where he studied the masterpieces of world painting and acquainted himself with the works by Rafael, Rembrandt, Titian, Veronese and Velazquez. Returning to Russia, Surikov commenced the work over Boyarynia Morozova, a long cherished picture. The historical basis of the picture is the Great Schism, the split of Russian church as a result of the struggle between traditional religious beliefs and new concepts forcefully introduced by the state against the will of part of the people. One of the most ardent defenders of the Old Belief was the noble boyarynia Feodosia Morozova, who, as a result, was confined in a convent by the Tsar. As the subject of the picture Surikov chose the moment when the boyarynia, draped in chains, was driven in a peasant's sled along the streets of Moscow to be humiliated and mocked at — by the crowd. Preparatory work took the master four years, when he made dozens of sketches and studies. The centre of the composition was to be the sled carrying the boyarynia through the mass of people; the emotional centre is the figure of the boyarynia, her terrifically expressive face, pale with fanatism, with fiercely glowing eyes and dry lips. Her raised hand extends two fingers making the sign of the cross, traditional sign of the Old Believers. The people around are represented by the artist as individual personalities, each having a peculiar character and appearance. The contrast of the black velvet coat of the boyarynia against the bright colours of the crowd and the whiteness of the snow creates a tragic effect. The colouristic range of the picture itself serves the purpose of enhancing the emotional significance of the events depicted. The profundity of ideas and perfection of artistic form place the picture among the highest achievements of Russian history painting. In the 1890s Surikov turned to another theme of Russian history, very close to his nature and artistic position; he painted Yermak Conquering Siberia (1895). Being a Cossack by birth, Surikov believed that his ancestors had come to Siberia with Yermak's army. Yermak Timofeyevich was the Cossack hetman, chief of a free Cossack army and was loved by the people as a hero, protector of the poor, and a fighter for freedom. In the 1580s, Tsar Ivan the Terrible summoned Yermak's army for the march to conquer Siberia, which was still under the Tartar Khan. At the Irtysh river the Cossacks lead by Yermak defeated the army of Khan Kuchum and thus consolidated the addition of the Siberian lands to Russia. It is this battle that Surikov depicted on his canvas. He had been collecting the material for this picture for several years travelling in the lands conquered by Yermak's army, studying the life, customs and traditions of the local peoples, making sketches of folk types, of old garments and weapons. The general impression of the picture is the grandness of the battle, enormity of the people's collision. «Two storms meet», are Surikov's words about the action. The artist's attention is equally sympathetic to each participant of the battle, be lie on the side of the Cossacks or in the ranks of the manytribal troop of Kuchum. Surikov rendered the intensity of the violent clash of masses as well as the mood and state of every warrior. There is no nationalistic colouring in the picture, no preference is shown to the Russians; the emphasis is on the mighty opposition of hostile forces. The painter found original colours for rendering both the brave faces and bright coats of the Cossacks and the Mongoloid faces with high cheekbones and the fur garments of the Tartar tribes. Surikov was sure that every nationality has a beauty of its own. The next picture is Suvorov Crossing the Alps (1899), a work that discloses the unique bravery of the Russian soldiers, their love and selfless devotion to their leader, Alexander Suvorov. The artist confronted a very difficult compositional and technical problem of creating the effect of the bodies practically dropping from the icy summit into the precipice. For that purpose he made the canvas vertically elongated and drew the figures in highly dynamic postures. Dedicated to his realistic method, Surikov went to Switzerland, to the place where Suvorov's army performed the crossing, climbed high to the mountains and made sketches and landscapes there and even slid down from the summit himself to experience the sensation of dropping. Surikov always cared for the images of folk heroes, such as Pugachev, Stepan Razin, Yermak, heroes whom the people sang songs and told legends about. There are many sketches and portraits of these characters among the artist's works. Finally, this interest resulted in a big canvas, Stepan Razin, which was finished in 1910 after years of preliminary work, studies and variants. The folklore motif of Stepan Razin and the Persian princess, whom he threw into the water to appease his companions, acquired a significance of a narrative about the fate of the people's movement in Tzarist Russia. The last picture by Surikov, Princess Visiting a Nunnery (1912), though made by an elderly person, is exeptionally intense and bright in colour. Artistic effect is based on a striking contrast between the vigorous youth of the Princess, dressed in precious clothes, and solemn, gloomy figures of nuns. Alongside of the history pictures the master created many portraits, mostly of Siberian women dressed in old Russian attires. He also made several interesting selfportraits executed at various periods of his life, and plenty of exquisite colourful watercolours. Vasily Surikov died in 1916 in Moscow.

|

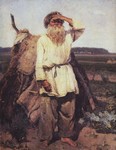

В. И. Суриков Покорение Сибири Ермаком, 1895 |  В. И. Суриков Портрет дочери Ольги с куклой, 1888 |  В. И. Суриков Венеция. Палаццо дожей, 1900 |  В. И. Суриков Старик-огородник, 1882 |  В. И. Суриков Вид Москвы, 1908 |

| © 2026 «Товарищество передвижных художественных выставок» |