|

на правах рекламы• Тут источник полезных советов по дому. |

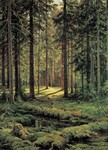

SummaryIvan Shishkin holds a place of honour in the history of Russian art. His name is inseparably connected with the development of Russian landscape painting in the second half of the nineteenth century. The works of this outstanding artist enjoy vast popularity; the best of them have become the classics of Russian painting. Over the forty years of his artistic activity Shishkin produced hundreds of paintings, thousands of studies and drawings, and a large number of engravings. Chronologically Shishkin's work is linked to the period of the evolution flourishing of critical realism in art. Having taken up painting back in the 1850s, at the time of the emergence of the Russian realist school, he was the only representative of the older generation of landscape artists to finish his creative career in the late nineteenth century. Already in his first independent works Shishkin tended towards a realistically accurate reproduction of nature in all the wealth and variety of its vegetable forms. The painter, however, not merely sought to achieve verisimilitude but tried to reveal the most meaningful and salient features of Russian nature. None of his predecessors had attached such importance to its study. In the words of Ivan Kramskoi, another leading Russian artist and theoretician of realism, Shishkin's was the «living school» based on a painstaking analysis of natural forms, on the impeccable drawing and on a constant search for new means of expression. Nature nourished his art and enabled him to fully reveal his talent. Studies and especially pencil sketches were indispensable to the artist's work on a picture. They helped him to resolve the problems of composition, rhythm and colour. Shishkin was the initiator not only of an analytical approach to nature but also of its treatment on a grand scale. During the 1870s and especially the 1880s—the period of his creative maturity — the in-depth typification and the epic scope became the distinguishing features of his best canvases. He saw landscape painting as a vehice for extolling the might and majesty of nature. This concept found a convincing reflection in his portrayal of Russian forests, fields and meadows — images evocative of optimism and pride. Shishkin's work dovetailed with the aims and purposes of the new school of painting which stood for a democratic art and the assertion of positive ideals. Among the Russian landscape painters Shishkin was the staunchest and most consistent exponent of the materialist aesthetics of Nikolai Chernyshevsky, who called on artists to depict nature in all its pure, unadorned beauty. In the late 1890s, when a new generation appeared on the Russian art scene and when great changes took place in Russian art, Shishkin remained faithful to these aesthetic principles. Ivan Shishkin was born in 1832 in Yelabuga, a small provincial town situated on the high bank of the Kama River amidst the austere, majestic forests. The impressions of childhood left a deep imprint on his mind. At the age of twenty Shishkin enrolled in the Moscow School of Painting and Sculpture, where his bent for landscape manifested itself at once. A three-years' training at the school which widely used the progressive pedagogical system of Alexei Venetsianov, based on an attentive and loving attitude to nature, was extremely fruitful for shaping Shishkin's artistic individuality. «The unconditional imitation of nature alone is quite enough to satisfy a landscape painter», he wrote in his copy-book. To come close to nature was his main goal at the time. One of the young man's earliest picture, Harvesting, shows that the sources of his art which absorbed many traditions of the Russian landscape painting of the first half of the nineteenth century, should be first of all sought in the Venetsianov school. It is worthy of note, however, that the entire youthful experience of Shishkin, his first-hand impressions and those coming from Venetsianov, Mikhail Lebedev and Western European artists, were to become so thoroughly reworked that it is virtually impossible to discern the stamp of some or other unfluence in Shishkin's highly original work. Apollon Mokritsky, his teacher at the Moscow school, did much to encourage and develop the young man's talents. Under his supervision, Shishkin executed a whole series of drawings of various plants. These efforts marked the beginnig of the analytical, «laboratory» work which did not cease throughout his life. A born draughtsman, relying on line and open stroke, Shishkin from the very start regarded the drawing as a means indispensable to the study of nature. Drawings, incidentally, comprise not only the largest part of the artist's legacy, but perhaps also the one most beloved by him. To perfect his skills, Shishkin entered, in 1856, the Academy of Arts. From that time on, his creative biography was closely linked with St Petersburg, where he lived to his dying day. During his training at the Academy, where after the death of Maxim Vorobyov there was no instructor who could teach him anything new, it was nature itself that became his principal instructor. Out there, face to face with nature, he groped for his independent artistic idiom. Nonetheless, the classical-romantic trend of academic landscape, which had taken its definitive form in the 1830s and 1840s, also left a mark on his evolution as an artist. Since the Academy inculcated in its pupils the imitation and even the direct copying of Western European artists, certain canonized devices inevitably penetrated the work of the young students, in a measure levelling their creativity. Shishkin was perhaps least of all affected by this «imitation disease», displaying a certain degree of independence. The influence of Alexandre Calame, a teacher especially revered at the Academy, was shortlived, leaving no trace in the artist's later work. Among the Academy students Shishkin very soon distinguished himself for his ingenuity, solid knowledge and brilliant abilities. His pencil and charcoal drawings won prizes and evoked general admiration. Shishkin's works of the Academy period bore the imprint of Romanticism, but it was rather a tribute to. the then dominant tradition. Meanwhile his approach to nature became increasingly sober and thoughtful. The artist derived particular use from plein-air studies on Valaam Island, known for its austere and picturesque beauty. This serious practice enabled him to clearly realize the problems of landscape painting. The Valaam motifs occur in a number of his canvases, including the View of Valaam Island. Kukko (1860), which he presented for a competition. The picture won Shishkin a large gold medal and a three-year scholarship to continue his studies abroad. Already at this time he displayed an extraordinary knowledge of plants and an astonishing skill to render their individual forms. During his training at the Academy Shishkin's world outlook matured in the conditions of a democratic upsurge which swept the progressive layers of Russian society at the turn of the 1860s. This landscape painter with a brilliant future lying before him, belonged to the circle of the artistic youth brought up on the materialist aesthetics and the new realist literature. These young men challenged the art divorced from contemporary reality and rebelled against the bureacratic routine that reigned at the Academy. Between 1862 and 1865 Shishkin lived on an Academy grant in Germany and Switzerland. As a result of six months' work in the studio of Rudolf Roller in Zurich and of his independent intensive efforts, the artist succeeded to markedly improve his professional skills. In the summer of 1864 he painted and drew from nature in the Teutoburg Forest; the rest of the time was spent in Düsseldorf. His foreign landscapes involved certain decorative features and stereotyped compositional schemes. As follows from Shishkin's letters, he looked on these works with a critical eye, which served as a guarantee for the successful development of his style and manner. The first-hand contacts with foreign artists eventually enabled Shishkin to formulate his own ideological and creative credo — a credo also shaped by his growing criticism of the Academy's education system. In 1865 Shishkin painted his View in the Vicinity of Düsseldorf for which he was awarded the title of Academician and which was shown at the 1867 World Fair in Paris. With this picture the early stage of the artist's areer, a stage of protracted apprenticeship, came to an end. During his stay abroad Shishkin not only produced paintings but also engaged in lithography and etching. His numerous pen drawings caught the eye of the Düsseldorf public and critics by their virtuoso hatching and filigree treatment of detail. On his return home, in the summer of 1865, Shishkin's achievements as a draughtsman received wide critical acclaim. A kind of milestone in Shishkin's creative biography was his trip to the village of Bratsevo near Moscow, undertaken in 1866. There he executed a study and the picture Midday in the Neighbourhood of Moscow (1869), based on it, which marked the beginning of his career as an original, national landscape artist. The merits of his works lie not only in their abundance of light, the masterly portrayal of far-flung fields and the lack of stereotyped compositional devices, but also in his landscapes' genuinely Russian, poetic flavour and epic majesty. The 1860s saw the formation of the new, democratic, school of Russian landscape painting. Towards the second half of the decade such artists as Alexei Savrasov, Mikhail Klodt and Lev Kamenev already embarked on the path of the realistic depiction of Russian scenery. It was the same goal that inspired Shishkin. Achieving the maximum concreteness of an image in a whole number of his works, seeking to show nature in all its simplicity, dispensing with no seemingly negligible detail, Shishkin more and more confidently moved away from the «invented academic landscape». His scrupulous reproduction of nature stood in sharp contrast to the academic canons of landscape painting. Shishkin's well-grounded creative method echoed the interest in exact sciences and particularly in natural sciences, characteristic of the time. Affirming this new realistic method, which shattered the foundations of the pseudo-romantic landscape, Shishkin signally contributed to the development of Russian art. The clear realization of the current artistic tasks, the deeply rooted democratic outlook and the nonacceptance of the academic system eventually brought Shishkin to the milieu of the members of the Society of Travelling Exhibitions. Founded in 1870, this society played an extremely important part in the democratization of art and united, on a common ideological platform, most of the country's leading artists. Shishkin became one of the most persistent exponents of the Travellers movement in landscape painting. With the picture Pine Forest in Viatka Province (1872), which appeared at the First Travelling Exhibition in Moscow, Shishkin conclusively established his basic theme in art — that of magnificent Russian pine forests. An unhurried narration, a lucid artistic vocabulary and an abundance of keenly observed detail became the distinguishing features of his landscapes. His ability to evoke the feeling of man's immediate contact with nature, in the spirit of the Travellers' principles, was the artist's forte. Moreover, in his pictures the forest never suppresses man: it is austere, majestic but not forbidding. Shishkin's well-defined landscape images most often reflected the stable states of nature. He emphasized this stability by the compositional arrangement, not infrequently placing the mutually balancing groups of trees along the edges of the canvas and also resorting to frontal construction. As a result, many of this canvases are remarkable for their solemn tranquillity. The 1870s were an important and fruitful period in Shishkin's career, during which he painted a number of significant canvases and a host of superb studies. At the same time the artist widely experimented with etching. He set great store by the gravure printing technique which allowed him to draw easily, without effort, and to preserve the free and lively manner of line drawing. Stylistically similar to his paintings, the artist's brilliant prints are strikingly expressive and subtle in execution. In some of his works Shishkin attains high poetic generalization while retaining his characteristic, loving approach to detail. This is well illustrated by his Rye (1878), a life-asserting picture consonant with sentiments of the people who associate the might and wealth of nature with the «happiness and contentment of human life». This image in a measure develops the motif of the Midday in the Neighbourhood of Moscow, although now it is raised to the level of an epic poem about Russia. During the last third of the nineteenth century Russian landscape painting made enormous and rapid progress. In the 1870s, along with heartfelt, lyrical pictures by Alexei Savrasov, the originator of the so-called mood landscape, there appeared romantic canvases by Arkhip Kuinji, who excelled in lighting effects and colour contrasts. At the end of this decade, marvellous, genre landscapes were produced by Vasily Polenov, a leading spirit in the evolution of Russian plein-air painting. But the greatest success at that time was achieved by Shishkin. It would seem that having painted the Rye the artist reached the peak of his fame, yet new accomplishments lay in store before him. It was in fact during the two last decades of the nineteenth century that his talent as a landscapist sparkled with utmost brilliance. Shishkin produced many works, deriving his subject-matter mainly from the life of the Russian forests, meadows and fields. While the key features of his art largely remained unchanged, he continued to work out the creative principles evolved by the late 1870s. His finest landscapes of the period reflected the tendencies typical for the whole of Russian art but he re-interpreted them in a way peculiarly his own. The artist worked with enthusiasm on pictures of grand scope and epic mood, exxolling the nature of his Homeland. His aspiration to convey different states of nature, to achieve a greater expressiveness of images through the use of pure colours manifested itself as never before. On top of that, the artist also took care of the textural variety of his canvases. The landscape Amidst the Spreading Vale (1883) belongs to Shishkin's supreme achievements. It is the most spatial landscape in Russian painting. Another important picture, Woodland Vistas (1884), was inspired by a trip to his native Yelabuga. This is also a deeply poetical image imbued with a sense of Nature's greatness. It should be pointed out that Shishkin aspired not only to monumentalize images but also to achieve the emotional, plein-air quality in his pictures. Perhaps the most remarkable result of the latter approach is his large study Pine-trees Lit Up by the Sun (1886), in which the artist, by means of reflexes and colour shadows, creates the impression of natural sunlight, at the same time accurately rendering the material objects. In his studies Shishkin's talent revealed itself with utmost power and ingenuity. While preserving the sensation of alive, spontaneously observed nature, they approximate to finished pictures. In their artistic merit, many of Shishkin's drawings can vie with the best of his paintings. Shishkin had a perfect command of any graphic technique, and his pencil, charcoal and pen drawings are as impeccable as his sheets done by brush. During the 1880s Shishkin arrived at a new understanding of the finished drawing, although he retained the light, dynamic manner of his earlier sketches. In his later period the artist devoted much effort to etchings which are notable for their virtuoso execution, striking beauty and conceptual profundity. As a landscape engraver Shishkin had no rivals in Russian art. An enormous plastic force combined with a sense of the light-and-air medium characterize his famous canvases Oak Grove and Oaks (both 1887). In 1889 he produced his landscape Morning in a Pine Forest which was to become the most popular in his entire legacy. Like another well-known work, Rain in a Oak Forest (1891), it brings out all the radiant beauty of the Russian scenery. In the last decade of his life Shishkin continued to work with an amazing creative vigour. The role of light in his landscapes increased significantly, as did his mastery of colour, while the perception of nature became more heartfelt, in line with the generally lyrical trend in Russian landscape painting at the time. Yet, resolving the tasks peculiar to the art of his day and further complicating his handwriting, Shishkin remained faithful to his own manner and style, relying on strict drawing, well-defined contours and meticulous rendition of the material world. The painting Mast-tree Grove (1898) consummated the artist's integral and original work. It combines the realistic concreteness of the image with broad generalization and typification. The sunlit powerful trunks of the age-old pines are painted with amazing skill. No other Russian artist could surpass Shishkin in the depiction of coniferous forests. The implementation of such a magnificent monumental concept as the Mast-tree Grove shows that the sixty-six-year-old painter was in the prime of his creative powers, but with this picture his artistic career was cut short. He died in his studio at the easel on which stood a newly begin canvas, The Sylvan Kingdom. Shishkin's role in Russian art did not lose its significance even in the years which saw the appearance of splendid landscapes by Isaac Levitan, Valentin Serov and Konstantin Korovin. Despite the fact that he espoused different aesthetic principles and advocated a different artistic system, Shishkin enjoyed an indisputable authority among the young Russian painters of the late nineteenth century. The new generation did not fail to acknowledge him as a thoughtful and masterful portrayer of Russian nature of which he was a connusseoir par excellence. In the complex, controversial artistic life at the close of the nineteenth century Shishkin remained a true and brilliant exponent of critical realism and democratic ideals in art. Irina Shuvalova

|

И. И. Шишкин Хвойный лес. Солнечный день |  И. И. Шишкин Около дачи |  И. И. Шишкин Дубки |  И. И. Шишкин Сосновый бор. Мачтовый лес в Вятской губернии |  И. И. Шишкин «Среди долины ровныя ...« |

| © 2024 «Товарищество передвижных художественных выставок» |